Pio Abad Excavates the Marcos Regime's Loot and Lies in 'Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts'

London-based Filipino artist Pio Abad attempts to wear many hats in "Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts." He is at once forensic examiner, archaeologist, exorcist, and scholar of history in this clear-eyed unraveling and unearthing of the loot, lies, and chicanery of the Marcos regime.

The son of activists Butch and Dina, Abad turns to his parents and their advocacy as his main reference point in this grounded artistic praxis.

Butch and Dina's work in the 1970s as community organizers of the social democratic movement during the Marcos regime had led to their eventual arrest. In 1980, Jesuit priests led by Ateneo de Manila University president Fr. Jose A. Cruz negotiated the couple's release from incarceration given that they be held under "campus arrest" at the Ateneo.

It only makes sense, then, for Abad's transfixing exhibit to end at this very institution.

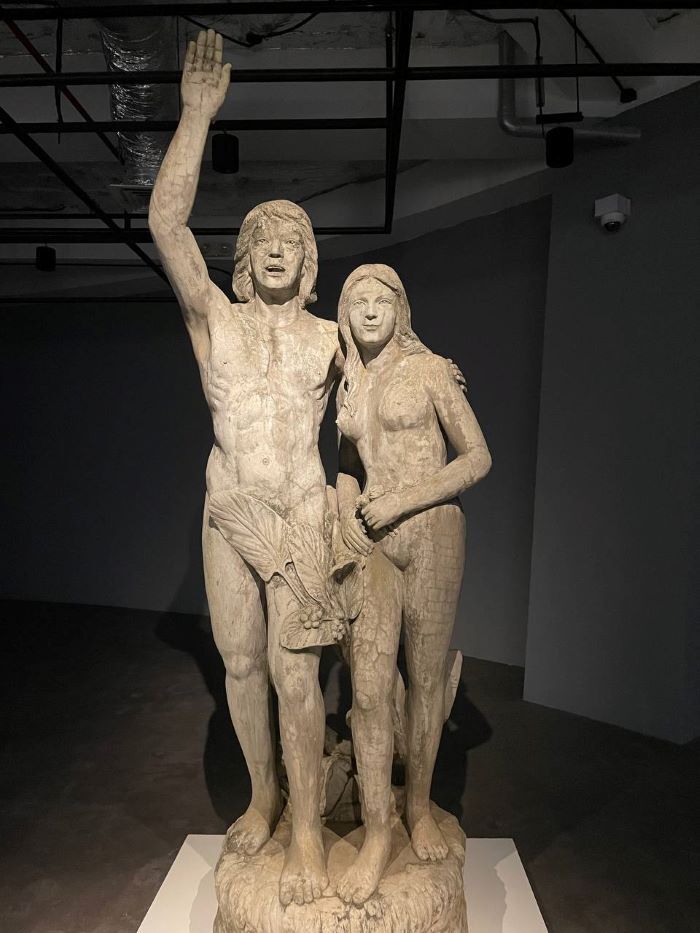

Malakas at Maganda

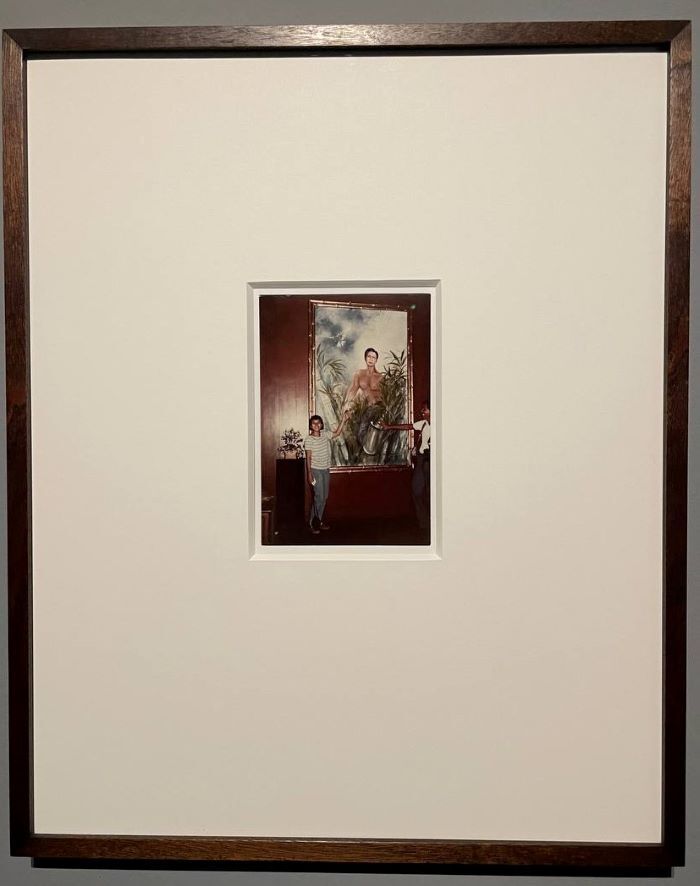

Housed on the third floor of the Ateneo Art Gallery in the Areté building, the exhibition starts with the gaze of Abad's mother, Dina, in the first room.

In one photograph, Dina can be seen inside Malacañang Palace posing next to a commissioned Evan Cosayo painting of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos depicted as the Philippine mythical figure Malakas.

Abad's parents were among the first protesters who entered the Marcoses' private chambers, where the painting was kept, just hours after the family was purged out of the country on Feb. 25, 1986, by the Filipino people during the EDSA Revolution.

In Philippine folklore, the first man and woman to exist were Malakas (the strong) and Maganda (the beautiful), who both emerged nude from a single bamboo stalk that was split by the pecking of a bird.

The dictator and his wife appropriated the folklore by taking on for themselves these mythological figures as representation for a conjugal dictatorship that operated under an ostensible banner: to make the nation prosperous once more.

It's this specific moment, Dina in the photo, that seemingly captured the breakdown of the regime's pretense of glory. As per Abad's exhibit notes, "[T]he nation that it had oppressed for decades had sudden access to the sordid private life behind it."

The Marcoses' pillaging of the country had been so immense that to even comprehend it requires the use of terminologies in the aggregate or collective sense: "loot, plunder, ill-gotten wealth." Yet in the comprehending of this vastness, the Marcoses' gains are rendered abstract and ambiguous. How and where does one even begin to fathom an estimated US$5 billion to US$10 billion worth of ill-gotten wealth and all its zeroes? Thousands of pairs of shoes? How to comprehend the thousands of lives disappeared, tortured, and killed?

Abad's exhibit, which spanned 10 years to put together, attempts to unravel the Marcoses' true greed in its almost unimaginable, staggering scale. Laying out objects and evidence piece by piece in "forensic fashion," it is a conscious exercise in specificity and active remembering — a necessary choreography against the threat of historical distortion.

In Abad's conversation with Filipino historian Ambeth Ocampo uploaded last May 6 by Ateneo Art Gallery, Ocampo told the artist that there is a need to call things for what they truly are to purge it.

"Even the Catholic rite of exorcism, you cannot drive the demon away unless you know its name and I think it's part of Philippine life that we call things by the wrong name and that's why we cannot exorcise," Ocampo said then. "In the sense if we don’t really see it as distortion, then people will keep saying it’s the Marcos' view of history, which validates itself."

Veering away from his mother's photograph, on another wall are two black paintings. These are actually fake copies of Cosayo's Malakas at Maganda paintings of Ferdinand and Imelda that Abad had created for display. When the late dictator was buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Cemetery of the Heroes) on Nov. 18, 2016, Abad decided to paint them over in black, thus erasing them.

In a small screen near the paintings, viewers can watch a clip of the painting-over of the counterfeit Malakas at Maganda.

"I wanted a counter offense to their erasure which is why I painted them black the day after the Supreme Court decision to bury," Abad had told Ocampo. "It seemed a feat to just keep on presenting these whimsical... and so it seemed like, 'If you're gonna erase, I'm gonna erase you.'"

Jane Ryan and William Saunders

In the next room is the second installation, "The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders," the artist's examination of the Marcoses' "imperial fantasies."

Jane Ryan and William Saunders were the fake identities that Imelda and Ferdinand used so they could open four accounts at Swiss bank Credit Suisse on March 20, 1968, four years before the declaration of martial law.

Ferdinand and Imelda used these accounts for the deposit of US$950,000. Abad, in his exhibit notes, identified just some of the things this amount was spent on: donating a million dollars to Richard Nixon's presidential campaigns, buying 40 Wall Street (now Trump Building), and purchasing expensive art, among others.

On one wall, Abad had displayed 40 prints of silverware that were sequestered from Ferdinand and Imelda and sold by Christie's representing the Philippine Commission on Good Government (PCGG).

In the middle, a row of postcard reproductions of Old Master paintings was laid out for exhibit guests to take as many, for free. These paintings on the postcards were among those also sequestered from the couple and sold by Christie's on behalf of the PCGG. On the back of these postcards are excerpts from different news articles about the Marcoses' loot.

On another wall, Abad hung ink sketches of sundries like furniture, Staffordshire porcelain, and other objects from the Marcoses’ spoils, which he described "served as a cloak of civility that masked their rampant criminality.”

The artist, in collaboration with his wife jeweler Frances Wadsworth Jones, continues the act of archiving and disentanglement in another installation that comprises 3D-printed resin replicas of Imelda’s jewelry. Stripped of their luster and gleam, the reproductions are a far cry from the glamour of the original gems.

Each reproduction has a label below it, which parses its astounding costs. For a pair of earrings and what appears to be a ring or brooch, the label reads, "1,726 agrarian reform beneficiaries by building farming capacities, providing access to services and developing enterprises." Under a tiara, "Four-year tuition for 2,000 college students in a Philippine state university."

The original jewelry collection by which these reproductions were based on was smuggled by the couple into the United States in 1986 upon their escape from the Philippines. With an estimated worth of US$21 million, the jewelry — known as the Hawaii Collection — were taken by the U.S. Customs when the Marcoses landed in Honolulu.

These were later repatriated to the Filipinos either for auction or liquidation, as per exhibit notes, but not before Rodrigo Duterte became president in 2016. While the Supreme Court had ruled the jewelry illegal acquisition, the jewelry collection remains vaulted in a bank somewhere in Manila.

Slime and Gene

Abad's last installation pays tribute to Slime Domingo and Gene Viernes, two leaders from the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP) who led the fight for democracy in the U.S. and the Philippines. Gene and Slime were assassinated in Seattle in June 1981 and their deaths were reportedly traced to the dictatorship through statements from one San Francisco-held company, Mabuhay Corporation. Its statements bore illegal expenditures, one of which is US$1 million between 1979 and 1989 in the U.S. for campaigns and a suspicious transaction classified as “special security projects.”

The row of acrylic paintings in this installation was Abad's own appropriation of the book covers of Ferdinand's manifestos. But by removing the text of these books or what the artist called the dictator's "political fictions," the paintings are reduced to "form and color" and thus transformed "into austere emblems of a nation that never was."

Through this process, Abad shared to Ocampo that he is able to transform his erasures into a productive, recuperative act and give tribute to those who truly fought against the Marcos regime, from community organizers and student activists to political leaders.

As a bookend to Abad's exhibition, which started with his late mother Dina's gaze, the last two paintings in "Slime and Gene" are dedicated to her, whose death from cancer in 2017 had shaped the making of the artist’s exhibit.

A Necessary Struggle

That Abad unveiled “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” last April 19 just weeks before the May 2022 elections was intentional. At that time, there was possibility, the possibility not just to imagine but to actually elect a leader who could lead the country to prosperity.

At 46 years past since the nation reclaimed its democracy from the clutches of the Marcoses, one sure is left with many questions over the current circumstances.

The reality now is that the son and namesake of the late dictator is the president. In a stunning landslide victory, Mr. Bongbong Marcos garnered 31.6 million votes or more than half of the electorate last May.

Bongbong had won under a sweeping message of unity – ambiguous though it was but perhaps that was the point – a flaw from the get-go for its failure if not blatant refusal to reconcile and seek to right the wrongs of the past. What unity? It never was.

But here we are. Yesterday, Aug. 3, two films about the Marcos regime premiered, one telling the so-called point of view of the dictator’s family and their supposed last 72 hours in Malacañang Palace and the other of the realities and struggles of those who fought against the dictatorship.

This is now a time when history can easily be branded as mere gossip or tsismis and when people seemingly deliberate of their ignorance and distortion of the facts feel prouder for it, shielded by the guise of a flawed “both-sides” story.

In his conversation with Ocampo, Abad had said that "the greatest form of imagination is the insistence of hope above... the most flagrant displays of cynicism..."

The exhibit succeeds in its capacity to offer resolution without being forthright in its anger. It is a stunning, sobering show that allures and seduces as much as it disturbs, and in Abad’s painstaking picking-apart of the Marcoses’ loot and lies and in the laying-out of evidence and research, viewers are compelled to see in focus.

But even in this boring-through, any artist, especially Abad, would admit that even art has its own limitations. Only those who are ready to be receptive to the message — to the truth — will understand the exhibition for what it stands for and what it is working towards. The necessary struggle now is to see without the blinkers.

“It's only in being able to see these things clearly that we can make the past present but also make sure the past isn’t our future,” he told Ocampo.

"I think it's recognizing that we're all part of a struggle that will outlive us but that doesn't mean we can't keep fighting for it."

Catch the last days of Pio Abad's "Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts," extended until Aug. 6, at the Ateneo Art Gallery.

Subscribe to The Beat's newsletter to receive compelling, curated content straight to your inbox! You can also create an account with us for free to start bookmarking articles for later reading.