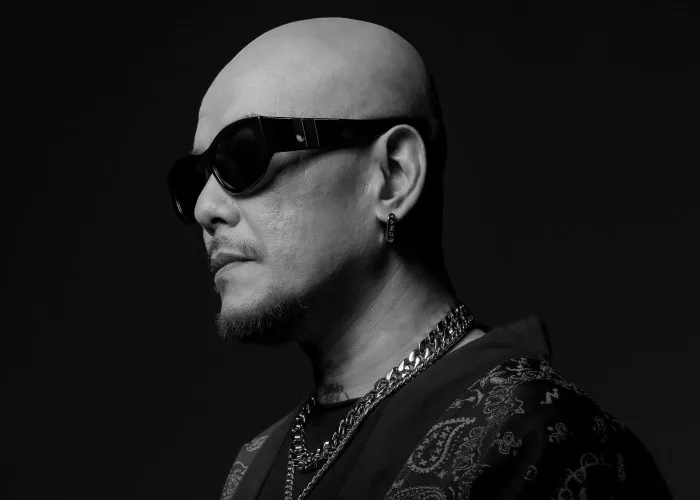

Mizuki Nishiyama Decodes Cultural Categories Through Vulnerability in Art

“It makes me sound a bit like a pyromaniac,” she says with an airy chuckle, “but it’s not quite so.”

Mizuki Nishiyama began her artistic career as a painter, recently branching out to tapestries, sculptures and performance art to explore more forms of expression. As an experimental multi-media artist, the classical elements of earth, air, fire, and water are some of Mizuki’s go-to organics when it comes to symbolising her layered cultural and personal identity for her tapestries.

Burning, weathering, and hacking come naturally to her, as she constantly plays back and forth with laborious processes involving movement and linearity. In many ways, the imperfections found in the physicality of creating her art are what makes its messaging ring true.

Known in the art world for her solo exhibitions in New York and Hong Kong, Mizuki’s provocative art draws from her cultural heritage as a Japanese artist from a mixed background. She has spent her career creating visceral, multi-layered artworks that bring a mirror to the human condition.

Speaking to The Beat Asia, Mizuki Nishiyama chats about her progression as a young Asian female artist, the chaotic methods she employs, and what mediums she plans to venture into next.

Born to a Japanese father and a Hong Kong mother, Mizuki felt her world was cut into segments from a young age. Many mixed and third-culture individuals share this sentiment, having grown up among different worlds with confused loyalties to the cultures that shaped them.

“I had to navigate by realizing that I needed to create my own puzzle pieces and put them together.”

Mizuki’s upbringing, or sodachi, is one that was heavily influenced by her father – with whom she shares many values and philosophies.

As a young Japanese man raised in the sixties and seventies, he was one of the few Japanese men that expanded into the influential Alta Moda world of Italy. It was there that he learned to blend his traditional Japanese virtues, customs, and way of thinking, into Italian craftsmanship.

“He’s a spectacular example of how to keep yourself intact, but also to realize that there’s so much beauty everywhere else.”

Now based in London, Mizuki has seen shifts in her art, created during her time in New York. From vibrant portraiture to entirely new mediums, the circuitous journey back to Hong Kong has been a unique landing pad for her to confront this idea of cultural belonging.

“I have one foot in and one foot out, and it’s always like that. It’s kind of a beauty, being able to see the East and West.”

Mizuki is deeply involved with decoding her current reality of living in a multi-cultural city, likening her artwork to a visual diary. Her body of work remains in a constant state of flux, like waves crashing onto to the shore to return to the ocean – finding new forms to exist the next time it breaches the land.

“I’m simply working things out. My artwork – whether it is the multi-layered aspect, or conceptual ideas – is a big mix of experiences, research, how you translate emotions into the physical form, and realising that… that’s not enough, either.”

And she’s right. How does one convey the utmost deepest vulnerabilities, fragilities, of being human? More importantly, how does one do it authentically?

For Mizuki, it’s as easy as surrendering to her curiosity. Sometimes this means putting your weight behind a palette and cutting through the viscosity of paints, other times, it means exploiting the tongues of a flame.

“It’s something that is bold,” says Mizuki, on the aesthetics of slashing with a palette. “I call my painting technique incisions, because they’re like cuts into these forms and figures.”

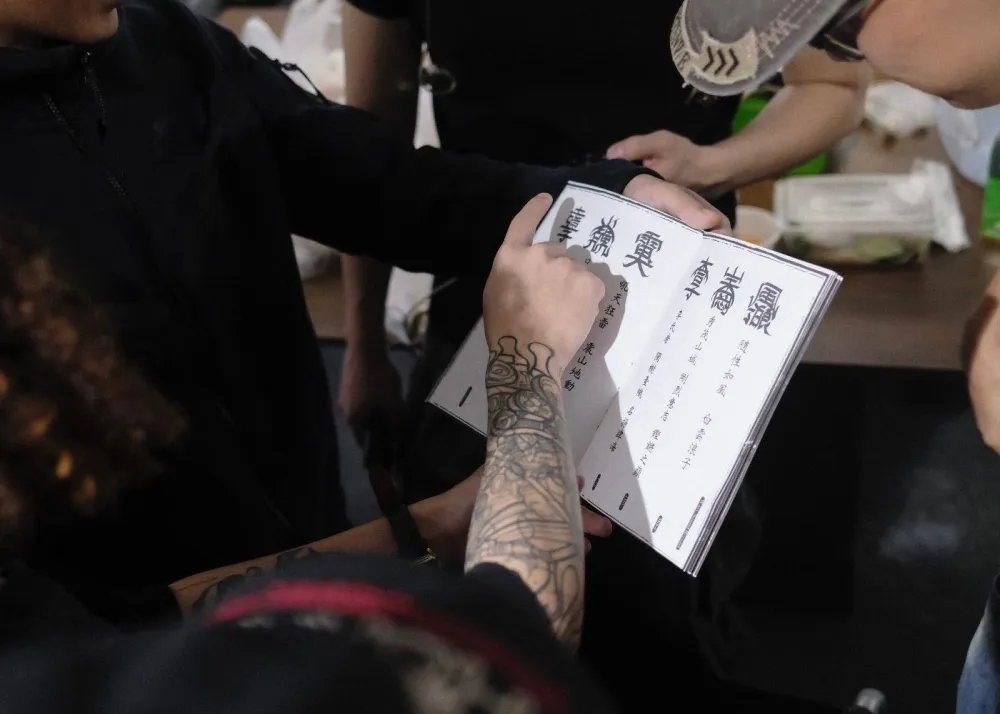

Her first endeavour into sculpturing saw Mizuki offering her own head as the subject, in a piece titled UMMA (2023). The claustrophobic creation process involves blocking four of the five senses whilst breathing out of two carefully placed straws in each nostril as she waited for the cast to harden in the dark.

Using a mix of bronze and her paternal soil from the 1400s for the final cast, Mizuki immortalises her present moment as a young woman, attempting to find connections with her heritage and memorialise her ‘Umma’ (the Hokkien term for grandmother).

On-lookers would notice the slightly crooked mouth, a tie to her grandmother’s appearance after she had suffered a stroke when Mizuki was young. An image that made her contemplate the confusing blend between the grotesque and comfort, leading to her research into the ‘beautiful and grotesque’ in connection to femininity and maternity.

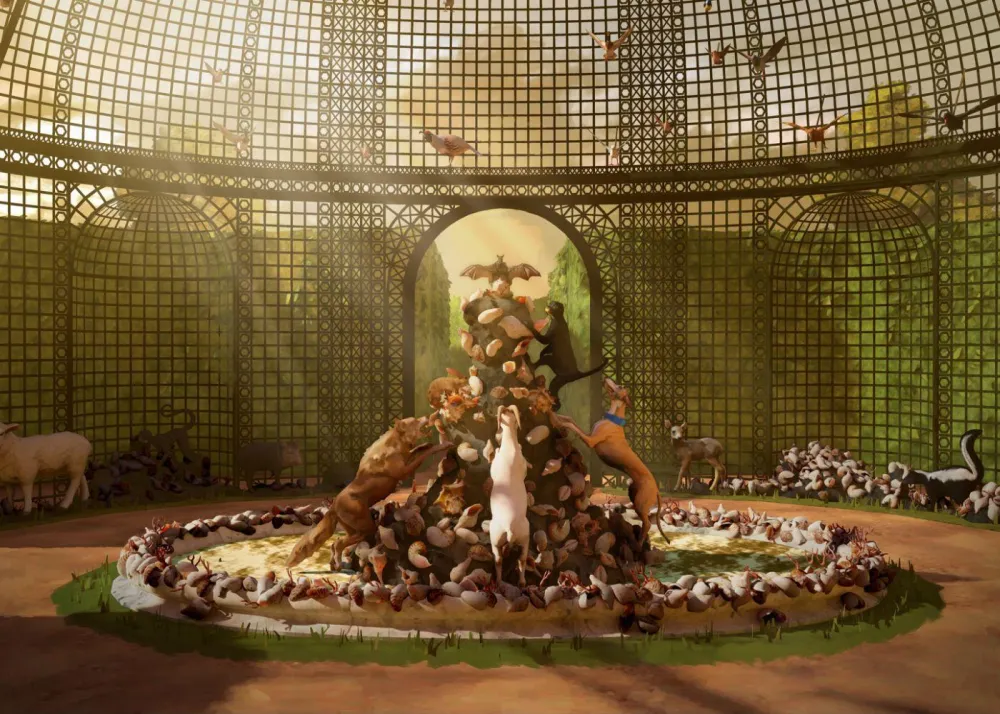

In another piece, a tapestry titled KAMI (2022), Mizuki gathered classical Japanese elements in a show of compelling symbolism. Centred around ancestry, God, and the patriarchy - she uses fire, earth, and water, to represent the carnage of women deemed ‘impure’ in accordance with their duplicities.

From burning and distressing the textiles, to burying the fabric in ancestral soil, she relies on the historic symbolism of the artworks’ materials and its associated thematic elements to convey a more nuanced reclamation of the feminine body.

After the burial, she rehydrates the distressed fabrics with London’s rainwater and Japanese immunity boosting teas as a symbolically feminine washing and nurturing of “God” (a method known as hydrofeminism). Finally, she reconstructed the textile using traditional Japanese embroidery.

In her artistic journey to get a little closer to what she wants to express, Mizuki hinted at performance art as her next project.

“I feel like I’m getting more and more loose around the edges, because I feel like it’s not enough anymore. I don’t want to feel restricted.”

The upcoming project sees Mizuki exploring her own physicality more than ever before in a way that is, in her words, both beautiful and grotesque.

"I do hope to make a full body cast in a room covered with soil and prepare a quasi-traditional Japanese funeral rite where I open my body up and take my reproductive system out. Wash it, Cleanse it.”

Drawing from the theme of purification, one of the pillars of Shintoism, the process is inspired by her current research into the relationship between the two themes and femininity.

“I know it’s going to be very emotional and physically difficult to execute the performance, let alone create the cast, but I want that entire nurturing and conflicting experience as a young woman – looking down into myself and having observers watch that process. It’s an invasive process but I am reclaiming my body and experiencing it first-hand.”

This strange concept of operating on herself, conducting her own funeral, allows Mizuki to reclaim these otherwise unachievable experiences through her art.

Keep up with Mizuki on her website or stay tuned with her next project on Instagram.

Get the latest curated content with The Beat Asia's newsletters. Sign up now for a weekly dose of the best stories, events, and deals delivered straight to your inbox. Don't miss out! Click here to subscribe.