Why Alena Murang’s Musical Sape Performances are a Cultural Treasure

An observation: even Alena Murang’s speaking voice is melodious; of course, this comes as no surprise to fans of the accomplished singer and musician. Known as one of the country’s most famous sape-players and performers, Alena’s repertoire includes music sung in the traditional though endangered languages of Kenyah and Kelabit.

According to Alena, there are only around 6,000 members of the Kelabit community; in that way, it seems doomed to remain under the shadows of other more prominent Austronesian languages. Yet, you would be surprised.

“I think sounds are a very powerful way to transmit languages,” Alena shared. “I’m always in awe of how many people are interested in sape music [and my songs] even though they do not understand the language; our culture is so niche but somehow people do resonate with it.”

Born to an English-Italian mother and a Serawakan father, Alena has always identified with the diversity of her cultures. Her parents had met in Malaysia, through common friends, while her mother was stationed in the country as a volunteer teacher. In fact, her generation was the first to be born outside of the longhouse and outside of the rainforest. “My father’s generation was the first to go to school,” she added.

With such close links to the indigenous way of life, Alena has grown up with a sincere appreciation for her background. Much of this is thanks to her mother, a former teacher and anthropologist, who had encouraged her daughter to explore the beauty of her roots as well.

“She pushed me to learn traditional dancing, she had traditional outfits made for me and bought me beads as well. She was also the one who pushed me to learn sape.”

For those who are unfamiliar, the sape is a traditional Kenyah instrument of Borneo origin. It is somewhat similar to a guitar or a ukulele, but is much more delicate. Alena plays the traditional sape; in contrast to the contemporary sape that is more mainstream in performances today.

“The sape is very sensitive to the touch of your hand on the strings and on the fret. You have to be very familiar with your sape, as in your own individual sape,” Alena shared. This kind of mindfulness towards the instrument is also what lends to the emotional fluence of it all. “[Sape music] is very meditative, it’s very calming. A lot of people say it feels like home,” Alena expounds.

The musician, who had grown up with the sape, shares that learning to play it was a very special time in her life. She was taught – alongside her cousins – by an uncle named Matthew; lessons were attended to religiously every Saturday, so much so that it would become almost ritualistic, eventually shaping Alena’s entire life and career.

The training sessions were meticulous but somewhat unorthodox. “We didn’t learn with any notations, or anything written down,” Alena recalled. “Everything was done by watching, listening to him play, and imitating him. We also had to learn tuning.” At the time, there were no sape tuners to turn to and so musicians did everything by ear.

Alena and her cousins carved their own frets, oiled their own sapes, and changed their own strings. Forming an intimate bond with their instruments, Matthew’s students were also taught to remain humble because – as Alena and her uncle put it – the sape is “an instrument of the community.”

Today, Alena’s songs touch on the idyllic themes of her somewhat traditional childhood. She writes songs that connect her listeners to themes of heritage, nature, and history.

“For my EP, ‘Flight,’ I wanted to tell the stories of [my] ancestors, my great ancestors who lived in the sky. And I wanted people to feel like they were flying in the heavens with them,” she shared. Produced by her cousin, Josh Maran, ‘Flight’ is a representation of three Kenyah folksongs and two Kelabit folksongs.

However, the Serawakan songbird does want to clarify one thing: that preservation is not her goal per se. “Preserving is what museums and archives do,” she explained. “For me, it’s about cultural evolution.” By allowing cultures to evolve with contemporary times, Alena believes that heritage is more likely to stay present and relevant. “Even my grandmother’s generation adapted songs for their times. They would take a traditional melody and adapt the lyrics to fit themes such as the [Indonesian-Malaysian] Confrontation War.”

Ultimately, what Alena wishes for indigenous communities is for them to be able to tell their own stories. Too often, romanticized ideas of minority communities are put on display and as Alena can attest, these sometimes do more harm than good, strengthening clichés and stereotypes about a community that is already so often misrepresented.

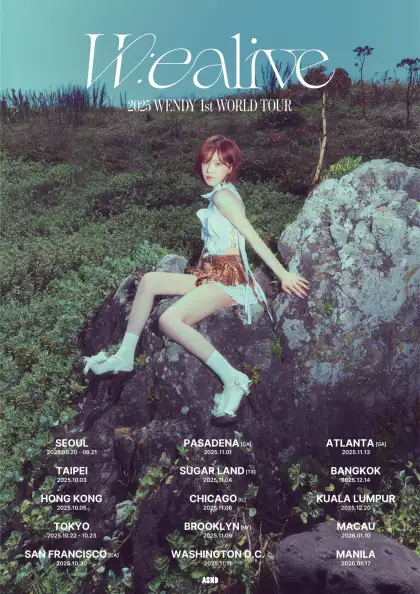

Fortunately, Alena continues to do exactly that – share accurate histories of her own indigenous upbringing. She has upcoming concerts in Taiwan this coming July and while she prefers to keep mum on other performances she does leave us with a newly released duet with Velvet Aduk. Entitled “Bejugit Betanda Menari (Dance Dance Dance)," the new release is an upbeat track that has accompanied happy celebrations during the Gawai Dayak holiday.

Get the latest curated content with The Beat Asia's newsletters. Sign up now for a weekly dose of the best stories, events, and deals delivered straight to your inbox. Don't miss out! Click here to subscribe.